No matter how hard he tried, Ivo Cubi could not have done anything else for a living. His last name, to begin with, in Italian literally means “Cubes.” Plus he was born into a family that, in one capacity or another, has worked with marble for seven generations. The sixth of which, his father, did everything possible to keep his only son on “the marble track.”

No matter how hard he tried, Ivo Cubi could not have done anything else for a living. His last name, to begin with, in Italian literally means “Cubes.” Plus he was born into a family that, in one capacity or another, has worked with marble for seven generations. The sixth of which, his father, did everything possible to keep his only son on “the marble track.”

After spending afternoons and holidays as a youth in the family’s marble lab, he decided at age 19 to go to South America as a geological scouting agent for a multinational corporation. “I was looking for adventure,” Ivo recalls. (He was born Angelo, but avoid confusion with his homonymous uncle, he was soon nicknamed after the priest who baptized him.) “I had a job lined up for me and all, but at the time, the legal adult age was 21 and you needed your parents’ signature to accept such a position. Of course, my father did not sign.”

As he relives the impasse, Cubi — a man in his early 60s with the relaxed posture, unassuming attire and piercing eyes — shrugs off a frustration that is still palpable. His vexation is mitigated by the awareness that, if his father had let him follow his early dream of roaming the hills of Bolivia and Venezuela in search for precious metals and oil, he probably would not have become what he is today: the marble king of New England, at least as far as high-end jobs are concerned.

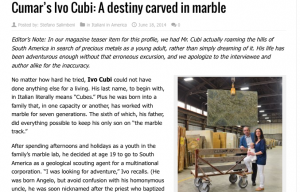

As we walk between endless rows of rectangular marble slabs arranged like a massive domino game, he explains how he personally selects the raw material from around the world, has them semi-finished in Italy, then brings them to America to be transformed into luxury surfaces for hotels, banks, offices and celebrity mansions. Here and there he points to marble already carved into irregular shapes and awaiting the finishing touches. “See this? This is going to go in the bathroom of a famous football player in Brookline. That over there will be the counter for the outside bar of the house that an airline tycoon owns in the Caribbean islands.”

I dare to ask him how much the finished product costs per square foot. “It depends on many factors,” he explains with an enthusiasm that shows a genuine love for the material itself and not only for the money it brings to his pockets. “It’s beauty, to start with; then it’s rarity and transportation; and most of all the difficulty of extracting it from places sometimes so remote that the owners of the caves have to build complex infrastructure just to get there.” He pauses, and while caressing a smooth, multicolored irregularly striped 7-foot-by-14-foot piece, notes, “This is one the most expensive: 500 dollars a square foot.”

As I struggle to calculate the overall value of the material contained in the storage area of his facility in Everett, we enter another sector, also huge and full of noisy, sophisticated machinery that cuts, carves and smoothes the marble, spraying cooling water at every step of the process. Further down is the finishing area, where the imperfections of the curves and the corners are corrected, by hand, by highly specialized workers trained by Ivo himself.

“I still consider myself a craftsman,” says Cubi, moving with ease through sparkles, water geysers, speedy forklifts and suspended marble rectangles as heavy as pick-up trucks. In Italy, he was in fact one of those craftsmen, working too hard and making too little by his own account, until one day in the mid-1980s, “A big American man with cigar in mouth” came to his lab. “‘How much do you make?’ he asked. ‘If you come to America to work for me, I’ll give you double.’” And Ivo went, leaving everything behind (not much really, after all debts were paid) and reinventing himself by working first in New York and then in Boston as somebody else’s employee.

But that didn’t last long. Even on this side of the ocean, the work was too much and the money too little. Moreover, seven generations of entrepreneurship in your DNA are hard to keep at bay. Sure enough, a few years later, Cubi started his own business by doing exactly the opposite of what everybody else was doing: Instead of importing marble from Italy to America he exported granite from New England to Italy.

The rest is a classic self-made entrepreneur success story: a story of endless working hours and of good investments at the right time. In Ivo’s case, it included dodging the recent global economic crisis by specializing in the only slice of the market — the highest end of it — that did not feel it, and by hiring an in-house team of engineers and architects focused solely on unique, exclusive, luxury projects. Although it is unfolding in snowy New England rather than in tropical South America, his professional parable was and still is quite an adventure.

“I owe everything to my fellow Italian immigrants who gave me help when I needed it the most,” he shares, showing more than a hint of emotion while sitting in an office where the eighth generation of Cubi Marble, his daughter, works and the ninth, his 2-year-old granddaughter, often plays. “Here, many good people came to my aid without expecting anything in return. In Italy, I am sorry to say, this does not happen, or at least it never happened to me.”