Apparently, Mario Motta has a successful medical career: Not only is he an established practicing cardiologist but he has also been the president of the Massachusetts Medical Association for many years. Yet he does not talk about it much. Actually, asking him about his job can be a somewhat frustrating Q&A, where the A is usually a brief, telegraphic sentence. The same can be said for questions about his family — although his three grown kids also have successful careers of their own — or any other “earthly” subject, for that matter.

Apparently, Mario Motta has a successful medical career: Not only is he an established practicing cardiologist but he has also been the president of the Massachusetts Medical Association for many years. Yet he does not talk about it much. Actually, asking him about his job can be a somewhat frustrating Q&A, where the A is usually a brief, telegraphic sentence. The same can be said for questions about his family — although his three grown kids also have successful careers of their own — or any other “earthly” subject, for that matter.

But when the conversation turns up — meaning towards the sky — there is absolutely no stopping him. Astronomy is what this soft-spoken, Sicilian-born doctor really wants to talk about. And when he does — even while he maintains his calm, reassuring tone — a dam of information, anecdotes and passion suddenly bursts open.

After all, his hobby (which he never defines as such) compelled him to create the world’s largest entirely homemade telescope and earned him an asteroid in his name — the highest recognition an amateur astronomer can receive. The distinction was a “thank you” gift for having donated a 32-inch lens to the Varese observatory. After funding ran out, it was the only indispensable piece missing for their telescope to be fully operational.

“Well you also could discover a comet,” he explains, “and in that case it will be immediately named after you. Or you could give your name to a crater on the moon, but most of them are already taken. Also, for that, you have to be famous … I mean Copernicus famous!” And he warns: motta-3“Do not believe those who are trying to sell you the right to name a star after you or your girlfriend: It’s a scam, like selling you the Brooklyn Bridge. Stars either have ancient Arabic names or are simply numbered by the International Astronomical Union, the only institution officially in charge.”

“Well you also could discover a comet,” he explains, “and in that case it will be immediately named after you. Or you could give your name to a crater on the moon, but most of them are already taken. Also, for that, you have to be famous … I mean Copernicus famous!” And he warns: motta-3“Do not believe those who are trying to sell you the right to name a star after you or your girlfriend: It’s a scam, like selling you the Brooklyn Bridge. Stars either have ancient Arabic names or are simply numbered by the International Astronomical Union, the only institution officially in charge.”

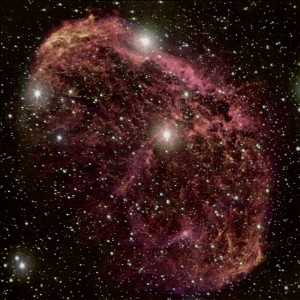

Mr. Motta knows well the laws regulating space, both natural and human ones. To begin with, he is an active member and past president of the American Association of Variable Stars Observers, the keepers of a database that professional astronomers often consult and quote in their scientific papers. “Variable stars are very young or very old ones,” explains Motta. “These are the times when they rapidly change in nature and brightness, enabling us to learn the most. You see, in their middle age, stars are dull and boring, just like people!” he adds with a sense of humor that also seems to kick in mostly when he’s talking about astronomy.

According to Motta, his head has always been among the stars. “My parents got me a toy telescope when I was 7, but soon I wanted something bigger and better,” he recalls. “They could not afford to buy it, so I started building it. By the age of 14 I had already ground my first mirror.” From then on, building the unaffordable became a habit with Motta. Many portable telescopes and three stationary ones later, Motta is the proud builder and owner of the largest, most powerful telescope ever made from scratch, mirrors and lenses included.

His computer-operated rotating monster sits in a fully automated dome on the roof of his Gloucester house, conveniently located as close to the sea as his wife would allow, while being as far away from city lights as possible. “It took four and a half years to build,” he explains, while sitting, with a gleam in his eye, at the controls of his “baby.”

“As far as the electronics and the mechanics of it go, let us say I have many smart friends who helped me out for free, so it only cost me $3 a pound, the average price of the scrap metal and the glass I used.” Considering that it weighs less than ton, a used midsize car would be more expensive.

“I spend most clear nights up here,” he says in such a matter-of-fact way that it sounds like the most normal thing in the world. “Fortunately, around here there are not as many clear nights in a year to make it a problem.”

At least by his own recount, nothing about his lifelong “space bug” seems to represent a problem, including synching up his vacations to coincide with solar eclipses. But why has he never done this for a living? As fate would have it, when an uncle suggested that he pursue a “real career,” he applied for and was accepted into medical school before he could even apply for a graduate program in physics. And the rest, as they say, is written in the stars. “This way,” he explains, not altogether convincingly, “I actually enjoy the best of both worlds.”