“If you love what you do, you don’t work a day in your life,” says Angelo Locilento as he somewhat reluctantly leaves his post at the counter of Tutto Italiano, where long lines of customers from all races, ages and walks of life wait to be served either some special product directly imported from Italy or some freshly made in-store treat.

“If you love what you do, you don’t work a day in your life,” says Angelo Locilento as he somewhat reluctantly leaves his post at the counter of Tutto Italiano, where long lines of customers from all races, ages and walks of life wait to be served either some special product directly imported from Italy or some freshly made in-store treat.

“Look! This is a fully functioning bakery that just finished making bread for the day,” he points out as we pass through the yeast-and-flour scented facility to his office.

After a careful look I see what he means.

The place is absolutely spotless. The metallic dough machine, the industrial electrical oven, the wooden boards where bread loaves and pizza pies destined for his four stores and a couple of selected restaurants were shaped by hand until an hour before, bear no trace of activity.

“Cleanliness, quality and attention to the customer: without these three elements constantly in mind you cannot possibly work for me,” he continues, and he means it.

During his 25 years of ownership of the Tutto Italiano food store and brand, he closed more satellite stores than he opened (mostly in affluent suburbs) and fired countless employees.

“I’d rather lose money than reputation,” he concludes as he sits down at his desk in his slightly claustrophobic, windowless office — clearly a place where he does not spend too much of his time.

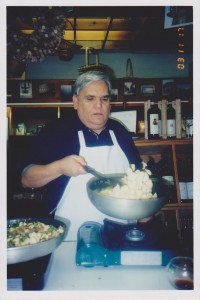

The pictures filling the walls, amid maps of his native and beloved Basilicata and icons of San Pio, clearly reveal what Locilento’s real turf is. No matter how old or young he appears to be, the sturdy yet surprisingly nimble 67-year-old entrepreneur is either wearing a soccer uniform or, in most cases, an apron — obviously his favorite item of clothing given that he never took off the one he was wearing during the entire interview.

The pictures filling the walls, amid maps of his native and beloved Basilicata and icons of San Pio, clearly reveal what Locilento’s real turf is. No matter how old or young he appears to be, the sturdy yet surprisingly nimble 67-year-old entrepreneur is either wearing a soccer uniform or, in most cases, an apron — obviously his favorite item of clothing given that he never took off the one he was wearing during the entire interview.

“Making food has always been my passion, even during the few years when it was not my job,” he recalls with a sparkle in his eyes that outshines the silver in his hair.

Born in Matera, Italy, of parents who owned a bakery and then a “salumeria” (cold cut and cured meat store), he has been surrounded by the food business since day one. At the age of 8 he began learning the ropes, and at 15 he opened his own store, turning it into a hangout for the workers of a nearby ceramics factory when he used a nearby soccer field to organize intramural corporate tournaments (making sure to sell drinks and snacks to the players).

But soon his entrepreneurial sprit started clashing with the asphyxiating (Italian bureaucracy and Angelo decided to come to America, New Jersey to be exact, where part of his extended family already owned a well-established shoemaking business. At first he worked for them on the Jersey side of the Hudson, then he opened his own slippers-producing facility across on Manhattan’s West side. But regardless of the money he made, happiness was not there: Happiness was in the kitchen! And that’s where Angelo returned as soon as the opportunity presented itself, by opening a small “alimentari” (grocery store), in Hudson County, N.J., which catered to the large Apulian immigrant community living there.

Then in 1987, during a trip to Boston, a “For Rent” sign on an unassuming storefront in the anything-but-strategically-located suburb of Hyde Park changed his life. In fact, it marked the spot where, from that moment on, he was going to spend most of it.

“For the first five years, I had no help. I would work the day shift, serving costumers at the counter while my wife rang them at the register, then I’d go home, sleep four hours, and come back at one in the morning to start the night shift making bread and getting things ready for the next day,” he racalls.

“For the first five years, I had no help. I would work the day shift, serving costumers at the counter while my wife rang them at the register, then I’d go home, sleep four hours, and come back at one in the morning to start the night shift making bread and getting things ready for the next day,” he racalls.

“Finally, from 7 to 9 a.m. I would sleep for another couple of hours on a bench and the day would start all over again.”

Amazingly Angelo makes this prison-camp tale sound almost like fun: For him it probably was. Just like it is today, with his “easy” 12 to 14 hours shifts, after which he unwinds by making food for family, friends or students in his cooking classes.

“Of course, back then it was mainly a matter of money,” he admits. “Also I have always been terrible at delegating.”

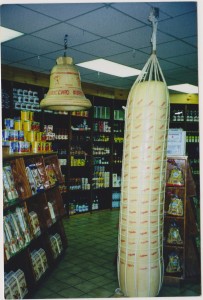

Obviously Mr. Tutto Italiano enjoys telling his life story. He knows, given the stunning success of his brand, both statewide and beyond, he must have done some something right. Yet after a while he gets restless again. He wants (he actually needs) to return to “not working” (as he describes it) amid a kaleidoscope of shelves neatly stacked with imported hard-to-find pastas and wines, hanging cured meats and cheeses, and a counter that is truly a feast of colors and flavors.

From the outside his flagship store for a quarter century may look anonymous, yet there is no shortage of customers. Upon our return from the office the lines were just as long as when we left for the interview and showed no signs of getting shorter anytime soon.

“You see, if I were downtown, or in the Italian neighborhood, many people would come in just to browse, but nobody drives all the way here just to look around,” he explains.

“You see, if I were downtown, or in the Italian neighborhood, many people would come in just to browse, but nobody drives all the way here just to look around,” he explains.

“I want people to buy, I like it when they do: not necessarily for the money, but because I want people to eat my food.”

“People,” in this particular case, included journalists, too. The prosciutto, mozzarella, basil and tomato sandwich he personally made me “for the road” was beyond delicious, and that comes as no surprise. Even water poured with that kind of passion has to taste good.