Un tentativo di spiegare la sitauzione politica italiana agli americani

pubblicato dal settimanale di Boston all’indomani del giuramento di Napolitano

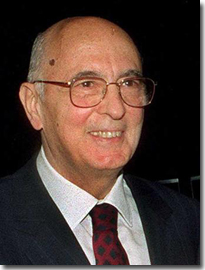

So, Italy finally has a president: not a brand new one, but at least it has one. And after two months of total stalling the, re-election (an unprecedented fact in Italian history) of 88 year-old Giorgio Napolitano to another seven year mandate as Head of State, is a definite step ahead for a parliament that since the February 25th vote has not managed to agree on anything at all, and a country which, in the midst of its worst crisis since World War II, is in desperate need of a functioning executive government.

So, Italy finally has a president: not a brand new one, but at least it has one. And after two months of total stalling the, re-election (an unprecedented fact in Italian history) of 88 year-old Giorgio Napolitano to another seven year mandate as Head of State, is a definite step ahead for a parliament that since the February 25th vote has not managed to agree on anything at all, and a country which, in the midst of its worst crisis since World War II, is in desperate need of a functioning executive government.

Now, the fact that there is a President does not automatically mean there will soon be a government. Especially considering the fact Napolitano already tried unsuccessfully in this past 56 days to form one.

In fact, due to a byzantine and inefficient electoral system, the vote two months ago created a parliament (especially in the Senate) evenly split in three: Silvio Berlusconi’s center right party- People of Liberty (PDL), Pierluigi Bersani’s center left party – Democratic Party (PD) and Beppe Grillo’s anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S); these three political forces were so far from each other (more ideologically, really, than in terms of programs) to the point of aprioristically refusing to govern in coalition with any of the other two.

After consulting with all the forces in the field, as provided by the Constitution, Mr. Napolitano tried anyway to make something happen, by giving Mr. Bersani as the leader of the party that came out of the election with a razor thin yet relative majority, the mandate to form some kind of a government. However, after running his own round of consultations and meetings, the head of PD could not come up with the necessary number of senators (50% +1) needed to grant a confidence vote to a possible cabinet of ministers of his choosing.

At that point the ball was back in Napolitano’s camp: yet being in the last semester of his seven-year mandate (the so-called “white semester”) the president could not dismiss the chambers of Parliament and send the country to another national election. All he could do was buy some time, and while waiting for the election of the new president scheduled for April 19th , appoint a special committee of ten so-called “wise men” (experts in the main fields of government) to come up with a national interest “to-do-list” for the next government (whatever its political color might be).

Then, finally, came the election of what everyone though was going to be Napolitano’s successor – little did we know it was going to be him again! According to the Italian constitution it is up to the parliament to do so: thus, it came as no surprise that an assembly that could not find an agreement on a government that, given the premises, could have lasted a few months could not agree on the name of someone who would hold the country’s highest office for the next seven years.

Few names were made, and voted on, from former Prime minister Romano Prodi to long time Labor Union leader Franco Marini, but the first five secret ballots revealed that disagreement ran high even within the single forces – in particular the PD – the leaders of which, as a result, all resigned their position, leaving the party at risk of crumbling into several different factions.

Then, last Friday, came the sixth round of voting, and the only name the left and the right (but not Grillo’s movement) seemed to agree on, was that of Giorgio Napolitano, the old veteran of Italian politics, who after being a member of the parliament for over sixty years, had oversaw it as the President for the past seven.

Then, last Friday, came the sixth round of voting, and the only name the left and the right (but not Grillo’s movement) seemed to agree on, was that of Giorgio Napolitano, the old veteran of Italian politics, who after being a member of the parliament for over sixty years, had oversaw it as the President for the past seven.

It was a clear landslide: 738 votes out of 997, many more than the 50% needed from the fitfh the round on (even more than the 66% needed for the first four). Yet it was a – just as clear – solution of last resort. Also considering the 88 year old president – who had already said many times he wanted to retire – had to be begged to accept the re-election.

In the end he did, like an old father who, one more time, takes his children out the trouble they are responsible for. But he made sure to scold, in an intensely emotional acceptance speech, each and every political party for not having been able to come up with much needed reforms (included the electoral system one that would have prevented the current stalemate from ever occurring) during over a year of Monti’s technical government. And for not being able, or wanting to, come up with some sort of an agreement over the last two months to give the country in deep economic and social trouble a desperately needed government.

“So far you have been deaf to my callings,” he said to the two chambers reunited amid loud cheer and applause (by the same people he actually came short of insulting) “and if I encounter the same deafness, I will make you face the consequences before the country.”

The “consequences” (dismissal of the Chambers for new elections or a resignation which will leave the parliament in the same quagmire it comes from) are clear to all and now, thanks to a freshly renewed mandate, Napolitano has the constitutional right to implement them at any given moment.

Hence, the left and the right have no other choice left other than comply: accept – together – whatever name he comes up with for Prime minister, vote – together – the confidence to whatever cabinet he or she will choose to put together, and quickly pass – together – the reforms suggested by the ten “wise men” a couple of weeks ago. In fact that is what both the leaders of PD and the PDL humbly said they will do, after visiting the president Tuesday for the latest – hopefully the last – round of consultations.

It all sounds awfully close to a presidential Republic – which Italy is not and definitely was not in the project of the drafters of the constitution who in 1948, with the fascist experience still fresh I their mind, probably exaggerated a bit wit the number of checks and balances.

Yet the alternative is an endless political, social and economic crisis the country can no longer afford and that will drag everyone – no one excluded – underwater. Grillo, who promises opposition already said the country will be bankrupt by October. But if a government is formed quickly, and most of all, holds itself together, chances are it will probably not.