Exasperated by austerity, Italians elect a parliament charged with anti-European resentment and bound to stalemate

So Italy voted , and made a mess… again! This time, though, it is not only impacting the country but also stock markets around the world — hit by the news of the Italian election results like a shock wave on Monday, scared to various degrees of drops and plunges. It began with Wall street, where the DOW had the lowest closing in four months (-216 points). Ripples followed through Asia and finished in Europe, with the Milan stock market losing a full 5 percent on Tuesday, right off the bat. The reason a national vote raised so much global concern can be found in the explosive combination of two worrisome keywords: gridlock and euro-skepticism.

So Italy voted , and made a mess… again! This time, though, it is not only impacting the country but also stock markets around the world — hit by the news of the Italian election results like a shock wave on Monday, scared to various degrees of drops and plunges. It began with Wall street, where the DOW had the lowest closing in four months (-216 points). Ripples followed through Asia and finished in Europe, with the Milan stock market losing a full 5 percent on Tuesday, right off the bat. The reason a national vote raised so much global concern can be found in the explosive combination of two worrisome keywords: gridlock and euro-skepticism.

Let us start from gridlock — Italian Style. Usually bad by definition, when it occurs in a so-called “parliamentary democracy” — where parliament not only passes laws but rather chooses everything from the presidents of the two Chambers, to the cabinet of ministers all the way to the president of the Republic — gridlock can be more paralyzing than in other variations, such as presidential democracies (like the US) or semi-presidential ones (like France).

This time, the gridlock is of the worst possible kind, as it involves three party coalitions with almost equal weight and no declared intention of allying with each other to form a parliamentary majority (and a fourth one which has the intention – but not the seats).

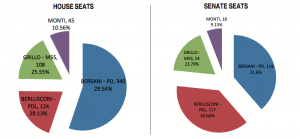

Basically, the Italian election boiled down to a four-horse race: the PD (the Democratic Party and its allies, the heavily favorite center left coalition headed by Pierluigi Bersani); the PDL (People of Liberty and its allies – including the Northern League -, a center right coalition headed by billionaire media mogul and four-times Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, who in only two months of savvy campaigning managed to recover a huge portion of his lost consensus); the Movimento 5 Stelle (Five star movement, a populist, grass roots movement inclined to radical reform and intending to “clean house,” headed by former comedian Beppe Grillo); the Lista Monti (Monti list, a centrist moderate group supported by economic elites and catholics headed by the current prime minister and aimed at continuing its pro-Europe fiscally responsible agenda).

Then came the results: numbers no one dared fully forecast but many — inside and out of Italy — had feared. It was basically a tie between the Bersani and Berlusconi coalitions, each with little more than 29 percent of the vote (with a tiny 0.4 percent edge for the former); a huge success for the Grillo Movement at over 25 percent and a just as big defeat for the Monti coalition, which barely made the minimum required number to have seats in both Houses with 10 percent of the vote.

In fact the “impossible majority” concerns only the Senate, where seats (and bonus seats for winning parties) are awarded on a regional basis. In the House matters are simpler: with the current electoral system the winner really takes it all, as 55% of its seats (340) are automatically given to the one party or coalition which obtained more votes (even if the difference is just a handful of votes- 120,000 in this case) so as to give that party a solid enough majority to rule.

In fact the “impossible majority” concerns only the Senate, where seats (and bonus seats for winning parties) are awarded on a regional basis. In the House matters are simpler: with the current electoral system the winner really takes it all, as 55% of its seats (340) are automatically given to the one party or coalition which obtained more votes (even if the difference is just a handful of votes- 120,000 in this case) so as to give that party a solid enough majority to rule.

But it is not enough. In the Senate the winner of each region is awarded a number of bonus seats, proportional to that region’s population. Hence, as it happened last Monday, if Italy’s 20 regions are split between the two major parties, no one reaches the magic number of 158 Senators. And if there is nobody else willing or able, or both, as is currently the case, to form a post election alliance, nothing gets done. Nothing!

To make matters worse, especially in the eyes of foreign governments and markets, is the fact that, although moving from very different, almost antipodal premises, both Berlusconi and Grillo based their electoral rhetoric on widespread mistrust and disappointment for the German-led European Union and the Euro which many (whether rightfully so or not) consider the main culprits of their economic hardships. They blame the rigor policies that being part of that system requires and that Monti so zealously implemented. In fact during his “technical” (Monti was appointed, not elected) one-year government, Italy recovered most of its lost international credibility, at the cost, however, of a general impoverishment of its citizens.

As a result, the parliament stemmed from last weekend’s vote actually has more than half of its members who belong to political forces that in various shapes, forms and with different levels of intensity, have publicly questioned or disowned altogether Italy’s belonging to the euro zone (to the point, in Grillo’s case, of calling for a referendum on the common currency). Not only the country was a founding member of the Union, but it is currently its second largest manufacturing economy (after Germany) and the third largest altogether. No wonder stock markets in Europe and around the world are throwing a fit.

Now, according to the Constitution, President of the Republic Giorgio Napolitano, at 85 years of age and near the end of his mandate, has the daunting task of designating the most likely party leader to form a majority able to support some kind of stable government. Needless to say, he has to do it quickly, as the longer the uncertainty lasts the worse it is for the economy. Whoever that leader will be (probably Bersani at this point) has two difficult aisles to reach across; one between him and a party with diametrically opposed views on just about anything, and another between him and a movement that never hid its intention of sending politicians as their main slogan says “tutti a casa” (everybody home). Unfortunately, the only easy aisle to cross, the one leading to Monti, and his meager dowry of 18 senators, is also irrelevant.